If poet Abby E. Murray were to describe in social media terms her relationship with the U.S. Army, it would probably be "it's complicated." She might love the Army, but only because her husband loves it. She doesn't always feel welcomed by it. And she definitely doesn't trust it.

Because, ultimately, the Army's job is to break things and hurt people. And who wants that?

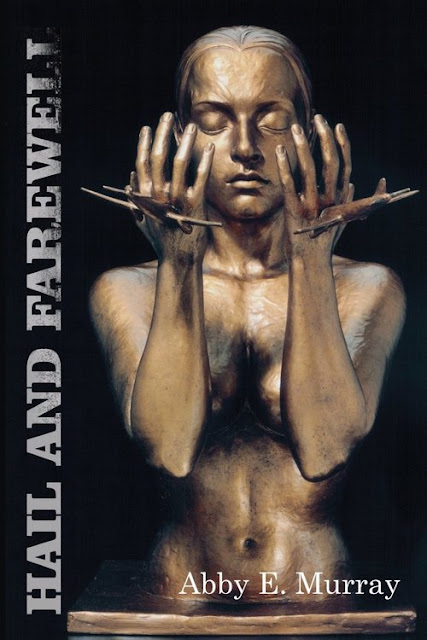

Murray's first book, the recently published and prize-winning "Hail and Farewell," is a collection of quirky, sometimes snarky, but always genuine explorations of Murray's relations to the Army and its cultural traditions, and with her active-duty soldier husband. It also notably interrogates struggles with pregnancy and parenthood. Some of the latter take place in the context of military family life, but one need not limit oneself to war to talk about conflict.

Like a cat, Murray chooses carefully when to engage a topic directly. Sometimes, she toys with it. Other times, she swats it off the table. Perhaps for reasons. Perhaps just to see what your reaction might be.

The collection's title evokes the tradition of sending-off soldiers to new assignments and locations with a small, informal ceremony. In many units, this is combined with a welcome of incoming personnel. In any form, such events are bittersweet milestones in the lives of individuals, but also of an organization. People come, people go, but the Army goes marching along.

In Murray's poems, such moments can variously take on the mythic tones of Catullus' "I salute you … now good-bye," to absurdism more in character with Groucho Marx's Captain Spaulding: "Hello, I must be going." For the most part, however, she aims at center-mass: good-humored, but unsentimental.

For example, Murray sets the stage for one ceremony in the collection's titular poem. Note the low-key commentaries present in "plastic tube" and "pub food," and in the commander's use of names, as well as the double-edged brilliance of "as if we are family":

Each time you are issued new ordersExposing more bite, she muses on a similar event in the separate poem "Hail and Farewell as a Junkyard Dog":

your current duty station hosts a Hail and Farewell:

the ceremony during which you receive a plaque

and I am given a rose in a plastic tube.

You make a short speech, your commander calls me

by your last name and rank, then we eat pub food

for the last time with the battalion as if we are family.

Every year, my colleagues ask what this means,

my friends whose jobs hail them by issuing paychecks

and say goodbye by letting them leave. […]

The colonel and his wifeMurray elevates this mix of awkwardness and affection to the sublime, when the "junkyard dog" pivots to again consider her husband. She is not there to be contrary, or to knock over punch bowls. She is there for reasons. And those reasons have little to do with the military.

are being sent to Fort Hood.

At their Hail and Farewell

I sit in the corner, a junkyard dog

on the overstuffed armchair.

The captain's wife asks me

if by going back to school

I will become a real doctor

or just the kind that writes.

Because I am a dog, I growl.

I do unladylike things:

show my teeth when I smile,

answer to my own whistle. […]

[…] I sit next to my husbandSuch a blend of mutual love and quiet regard seems worthy of its own ancient Greek nomenclature. Or perhaps there is an untranslatable German word, for something like "clear-eyed romance."

who is not a junkyard dog,

who smiles like he means it.

He places one finger

on the soft spot behind my ear

and I can hear his skin

telling me I've been so good.

Padding about on cat's paws throughout her collection, Murray similarly navigates a number of hard-fraught cultural practices in today's modern military. How married couples fretfully meet-up halfway around the world, for example, in the middle of a spouse's combat deployment. And the stuff-and-sputter of homecoming ceremonies. And "reintegration" seminars. Marriage-resilience workshops. Formal-dress Army birthday celebrations.

Murray's is a unique and wonderfully nuanced voice, in a growing klatch of unique and wonderfully nuanced voices: poets who happen to be related to war by marriage.

(For this reviewer, those voices include Jehanne Dubrow and Amalie Flynn, who write from their family experiences with the U.S. Navy; Lisa Stice, who writes from family experiences with the U.S. Marine Corps; and Elyse Fenton, who writes from family experiences with the U.S. Army. To this list add Lynn Marie Huston, who has published poetry about a relationship with a deployed soldier; and Charlie Bondhus, who has written about a relationship with a U.S. Marine. For a list of poetry written about 21st century wars involving the United States, visit here.)

Notably, Murray is the editor of Collateral journal, the mission of which is to draw attention to "the impact of violent conflict and military service by exploring experiences that surround the combat zone." She is more than a believer in poetry, she puts words into action. She teaches rhetorical writing techniques to Army officers, and poetry workshops to children held in detention centers.

It is no surprise then, that Murray hopes that her words and example will inspire others to take up pen and action. She dedicates her 99-page collection to other military spouses, "who see what happens during and after war, especially those still searching for their way to speak." In the back of the book, she notes, "My husband's experiences in the military and in combat have influenced my career as a poet and teacher. He operates in a culture that doesn't truly see me, and he has struggled, mostly with success, to question that."

Empathetic to both sides in the civil-military conversation, Murray keeps her observational barbs sharp, but cheery—she's like a Mary Poppins in combat boots. More often than not, her poems suggest a collaborative or confidential tone, rather than one of confrontation. For example, as she breezily starts her poem "International Women's Day":

The world observes my sexAnd this, from "How to Comfort a Small Child," a list of found and received advice on how best to act as a military parent:

on the same day America

celebrates the pancake,

and who doesn't love a good pancake?

[...] Make friends with womenWhere Murray stands out, above, and apart, however—where she "exceeds the standard," if you will—is in the way she tempers comparatively overt critiques of military culture and militarism, without tamping down her senses of humor, patriotism, or Storge (... und Drang?). In her longer poem "Happy Birthday, Army," she writes, for example:

who understand, women

with children and spouses

who haven't called in days.

When your daughter

flushes her plastic fox

down the toilet

and says he went to Afghanistan,

don't read into it.

Call a plumber.

[…] a woman's voice whispersMurray's depictions and images are intimate, her stories memorable, and her emotions immediate and accessible. With a feline grace, Murray reveals herself in glimpses, until you are comfortable with her work, and it is comfortable with you.

from beneath the howitzer,

the rented microphone

on fire with song:

Happy birrrthday, dear arrrmy

a la Marilyn Monroe,

and we are all a bunch of JFKs,

in our lace and heels

and cummerbunds and cords.

We watch a five-tiered cake

piped in black and gold buttercream

being pulled between our tables

by a silver robot

and shrug into the silk of knowing

we could end all this

with the flick of a finger

if we wanted.

When you achieve a certain level of mutual regard, it may curl up with you and purr. Other times, it may still scratch.

Because it is complicated.